Spontaneous Fat Loss vs. Caloric Restriction

A brief summary and elaboration of a point from a paper I recently published on energy signals on ketogenic diets (with special reference to effects on sleep).

From what I have studied, satiety appears to be a consequence of the recovery of metabolic rate to baseline levels [1]. After a meal, fuel availability eventually starts to decline, Along with it, energy production must also decline from lack of substrate. This decline in actual, produced energy triggers and corresponds to hunger. When we eat, fuel again becomes available, allowing energy production to rise, and this leads to the experience of satiation.

Satiation can really only be measured objectively by the moment of ceasing to eat, which is an all or nothing response. But it is usually experienced subjectively as a fuzzy line, such that you can finish your plate if there isn't much left or it's very delicious, even after you sense you've had enough. Under some circumstances, people feel a very sudden-onset "cement truck" satiation that is hard to eat past. This is reported a lot on Carnivore Diets, especially "KetoAF". It contrasts with ceasing to eat because you're tired of eating even though not satiated, which is sometimes reported on low fat, high protein diets. But the underlying sensation of "enough" is the one we're interested in, a physiological satiation, as opposed to stopping eating for other reasons.

These physiological satiation and hunger responses appear to be communicated through several mutually reinforcing signals indicating that energy access has returned. I have argued in the paper that the most important and universal of those appears to be ROS generation, which signals energy production itself, not just fuel availability. See the paper for details.

The implication of this is very important for understanding why ketogenic diets work the way they do for fat loss, and how it differs from how caloric restriction works.

How caloric restriction works for fat loss

In an ideal world, when you restrict calories, fat from your fat stores floods into the bloodstream getting delivered to cells and broken up to release chemical energy. To the degree that this is happening, you would not be hungry, because fuel access would be undisturbed and metabolic rate would not fall.

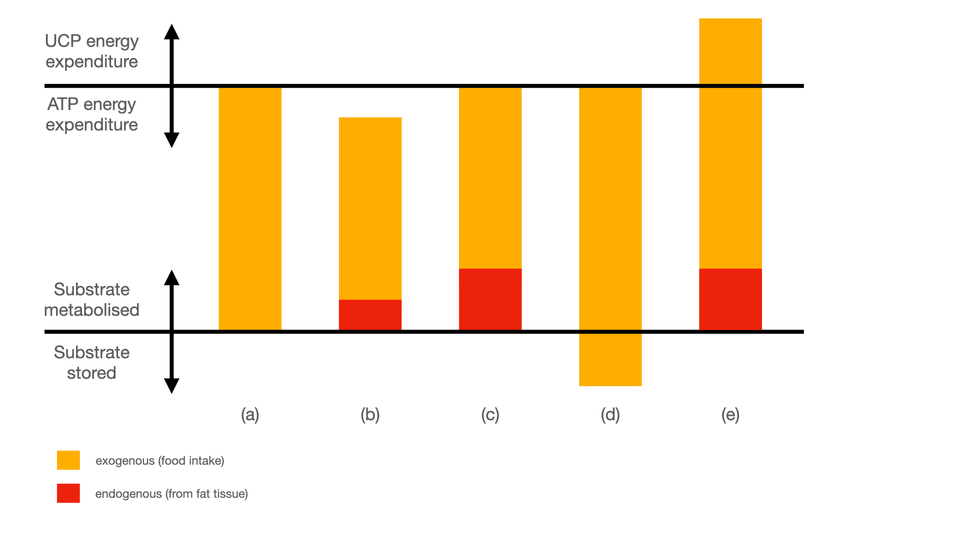

Therefore, the experience of feeling hungry when calorie restricted means that your fat stores are not providing for the entirety of the energy gap. That necessarily means that the deficit that you think you induced by eating x fewer calories than you thought you needed (a number that is never static in the first place) didn't in fact occur. This situation corresponds to part (b) of the diagram. You ate less, your fat stores made up some of the gap, but not all of it, so now you have less available energy and you feel it in the form of hunger. You probably also feel less... energetic. And maybe cold.

When is a deficit not a deficit?

Before we run into confusion, let's differentiate between two kinds of gaps, or "deficits".

One kind of "deficit" is the one that represents the difference between all the energy you produced in total and the amount you produced from the food you ate. Let's call this Energy-Produced-from-Body-Parts. This is imperfect as a description, because what actually happens is that some of what you ate is stored in exchange for some of what you used. We can ignore this for the moment; it doesn't impact the logic. But it can matter, for example, when we start looking at different kinds of fat.

People often intend to use the word deficit this way when they talk about restricting calories. They'll say "If I create a deficit of 750 calories a day I will lose one pound of fat in five days"--which is true if what they mean is actually using 750 calories worth of fat every day from their bodies (Energy-Produced-From-Body-Parts) to generate energy (without replenishment).

But here's where they take a leap. They start with some kind of fudgy calculation to estimate their daily caloric needs. Maybe it comes out to 2000 kcal. Then they'll assume that if they eat 750 calories less than that in a given day, the body will simply draw that exact amount from fat stores. But this isn't normally true.

It's false because fat is released and oxidized at a limited rate. When you reach the limit of how much fat you can burn, whether from normal rate limits on lipolysis (release of fat from stores), damaged or dysfunctional fat tissue, or issues on the oxidation rate side, that's it. You can't just make it burn faster because you want it to. Not all of Energy-Produced-From-Body-Parts comes from fat; it's always a combination of fat and lean mass. So what happens is as your ability to draw from your fat supply dwindles, the proportion of subtrate coming from lean mass catabolism increases. Non-ketogenic caloric restriction in particular is notorious for high rates of incidental lean mass loss. More on that below. Beyond that, though, you just have to make do with less. And we do.

That's where the second "deficit" comes in. I want to draw attention to the deficit between the amount of energy you need to produce to maintain baseline metabolic rate, and the amount you get from all sources (exogenous and endogenous) combined. Let's call this gap the Produced-Less-than-Required-Gap.

When you restrict calories to the point of hunger, the hunger itself is evidence that you Produced-Less-Than-Required, and it says nothing about how much you induced an increase in Energy-Produced-From-Body-Parts other than "not enough". If it was a significant amount, and you're willing to persist through the cost of inadequate energy (like tanking mood and libido), you can make this work to lose fat. But if it is a small amount or mostly comes from lean mass, this will either be impossible to sustain, or the results will be transient.

When you restrict calories and really aren't hungry and it causes you to lose weight, then you've leveraged enough Energy-Produced-From-Body-Parts to close the gap. Awesome! Either you have very good "metabolic flexibility (ability to upregulate fat release and storage under duress) or you were previously eating more than you needed for satiation; perhaps somewhere within a buffer zone before satiation hits too hard, or routinely eating beyond what feels good for some outside reason. I think this happens, but is not nearly as common a cause of overweight as some smug, naturally thin people assume. If it doesn't cause you to lose weight then you must have induced a small enough Produced-Less-Than-Required-Gap that it is within the bounds of satiation. In other words, your metabolic rate didn't go up quite as high as usual, but it was high enough to make you feel satiated.

How ketogenic diets work for fat loss

In contrast to restricting calories, ketogenic diets often result in spontaneous fat loss, that is, fat loss that occurs when eating until satiated (ad libitum). The fact that you are eating until satiated means that you have no significant deficit in terms of a Produced-Less-Than-Required-Gap. The fact that you lost fat implies that you did have a deficit in the Energy-Produced-From-Body-Parts sense. This corresponds to bar (c) in the diagram.

But that's astonishing isn't it?

A lot of people upon learning this conclude: Ketogenic diets cause weight loss by reducing appetite and thereby causing people to spontaneously reduce calories. Therefore, there is nothing "magic" going on, and it's just further proof that fat loss entails a caloric deficit (Energy-Produced-From-Body-Parts). It doesn't matter how you do it.

This conclusion misses the point and the "magic". The "magic" is that the ability to release fat from stores and oxidize it is so enhanced by a ketogenic diet (by multiple mechanisms) that you get most of your satiation through preventing the Produced-Less-Than-Required-Gap to even occur in the first place! This is why lean mass is so little compromised. The reason Energy-Produced-From-Body-Parts is increased isn't because the body is out of energy and looking for it anywhere indiscriminately, it's increased because the fat that was once locked away is now more available, even between meals.

This looks like "set point"

But it's not a set point of body fat that the body wants to maintain per se, as far as I can tell. As I described it in the paper, body fat does not appear to be the "parameter of regulation", rather, energy access is. The amount of body fat you will hold eating ad libitum appears to be a direct result of how much you can release and burn at a time, which is, to a first approximation governed by mass: all else equal, to get a higher rate of energy from fat, you need more stores, because there is a rate limit on lipolysis. Hence you have to store enough to match the rate of release required to meet your metabolic rate. If you do something that changes the rate of lipolysis then it might seem like your "mass set point" changed, but what changed is the amount of fat you need to hold to meet your energy needs. For example, with lower basal insulin, you can get your needs met with lower fat mass.

Note: I'm not saying that your body somehow detects how much mass it needs and "sets" it to that, though. This all happens passively as a result of fuel partitioning. If your fat stores don't release enough to keep you satiated you will eat more and thereby keep what you have. If they release enough but you can't oxidize it fast enough it will hang around in the bloodstream and look like diabetes, but you'll still be hungry. (More evidence that fuel alone is not an adequate signal of energy availability.)

What if you undereat on keto?

The thing is, the problem I described above with caloric restriction causing a Produced-Less-Than-Required-Gap happens whether or not you're on a ketogenic diet, if you eat below satiation. For some people, a ketogenic diet alone does not create a "set point" low enough for their liking (or they are just in a hurry), and so they combine ketogenic diets with caloric restriction. This could be because of unrealistic and unhealthy bodyfat goals, or because of health issues interfering with fat loss. Or there can be other reasons, such as an aversion to eating fat or unexplained excess loss of appetite [2].

When this happens, you still will get faster, more efficient fat loss from the ketogenic state, but you will also get all the issues with inadequate energy you would get with any prolonged caloric restriction, including fatigue, sex hormone deficits, and mood problems. This is not a "ketogenic diet" problem, or a "lack of carbs" problem. It's a lack of energy problem.

Chasing protein

Now, presuming you are starting from adequate amino acid intake, such that normal turnover is covered by your protein consumption, what would happen if you tried to force Energy-Produced-From-Body-Parts beyond what your fat stores can supply?

When you increase the Produced-Less-Than-Required-Gap because your fat mass can't keep up, normally you start catabolizing more lean mass and switching into Phase III starvation, where most of your energy comes from protein (see box). Other than eating up loose skin, no one wants that. So what's an already lean fellow to do if he's using caloric restriction to cut further and wants to prevent muscle loss from the necessary Produced-Less-Than-Required-Gap that results largely from fat mass being too low already to provide daily needs at normal rate constraints?

He could fill the gap with fat by eating just enough to hit satiation, but remember, in this scenario, he's trying to somehow force more. But forcing more Energy-Produced-From-Body-Parts will only cut into muscle. So what if he fills the gap with protein? Doing this switches you into Phase III metabolism, but the protein is coming from food instead of your lean mass. Because you always burn some fat, I think this can work in the ultra-lean to eek out more fat while protecting lean mass.

However there is a Catch-22, because the more protein you eat the more difficult it is to draw out the fat due to higher insulin. This vicious cycle leads to more hunger requiring more protein, as described in rabbit starvation accounts, and so the strategy only works if you're willing to endure all those symptoms described above. Some people think it's worth it. But it's totally unnecessary when going from overweight to normal wieght, and isn't without consequences.

Satiety is not a trick to reduce caloric intake

A key point to notice here is that satiety (the persistence of satiation over time) isn't a trick. You can't get there without fulfilling your energy needs and closing the Produced-Less-Than-Required-Gap.

So terms like satiety per calorie as a guide to how to eat to lose weight, can only make sense if what you're seeking is foods that actually cause you to increase Energy-Produced-From-Body-parts. If they do not do that, they will not create longer satiety. If they cause you to stop eating because they have "low hedonic value", say, or because they make you feel stuffed and uncomfortable, or because you are really hungry but you can't bear another bite of dry chicken breast, that's not physiological satiation, and it doesn't close the Produced-Less-Than-Required-Gap. These, then, are merely tricks to aid caloric restriction, not to cause spontaneous fat loss, and so they won't have the same benefits, even if they "work".

[1] For this and other relevant citations, please see O’Hearn, L. Amber. “Signals of Energy Availability in Sleep: Consequences of a Fat-Based Metabolism.” Frontiers in Nutrition 11 (August 29, 2024)..

[2] Sometimes it's not intentional. The appetite suppressing effects of ketosis sometimes seem to create a mild Produced-Less-Than-Required-Gap and still trip the satiation trigger. I don't know why.