The proverbial last 10 pounds

Even though I’m happy with the health effects of my diet, and my weight is stable in a healthy bracket, I still consider myself a little overfat. Having eliminated most plants from my diet, and given that I believe that weight loss arrived at by enduring hunger is likely to reflect loss of lean mass, not fat, one might think there was little left for me to try, but that’s not quite true. There are two obvious changes I could make. Possibly to the detriment of science, but in the interest of speed and because of the plausibility of synergy, I’ve decided to try both at once.

More Ketosis

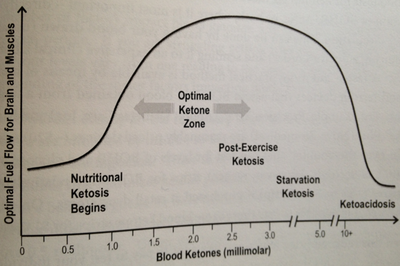

The first involves deepening my level of ketosis. Most of the times that I have measured the level of β-hydroxybutyrate in my blood, it has come out surprisingly low, maybe 0.2 to 0.4. This is much less than the Phinney-and-Volek-recommended nutritional ketosis range that starts at about 0.5 mMol. According to them, benefits increase until about 3.0 mMol. Here is the graphic from their book, which I borrowed without permission from Jimmy Moore. I hope he doesn’t mind.

I really don’t know what the y-axis means, but it’s clear what their recommendations are.

Given that I eat practically no carbohydrate, this low measurement is probably a reflection of my protein intake. Although the scientific evidence available on the inverse relationship between protein intake and ketosis in keto dieters is distinctly lacking, it appears to be true anyway. (I intend to write a post about that on my ketogenic science blog, but don’t hold your breath — it’s complex, and I’m a busy woman.)

I have chosen to leave the evidence of the link between my diet and my blood ketones somewhat unscientific, in that I am not tracking my food. I have tracked my food extensively in the past, and the problem with it is that the kinds of food I prefer to eat are not easy to analyze, because they aren’t uniform. For example:

- One piece of ribeye is fattier than another, especially if at this meal I’m eating the cap and at that meal I’m eating the center. Moreover, I often buy large, untrimmed pieces and leave the fat on. My steaks look more like this,

than this,

and so I distrust nutritional databases.

- How do I know how much of the bacon grease absorbed into my portion of the scrambled eggs, and if there are also pieces of bacon in it, do I need to take them back out and measure them separately or assume I got an amount proportional to what went in?

- The nutritional composition of homemade broths are anyone’s guess, particularly when there are bits of meat in it.

Because of this complication, when I did that tracking last time, I felt restricted to a subset of foods, and even then the imprecision bothered me. So I decided not to do it this time.

Nonetheless, I still get to develop my own intuitive sense of what’s going on by taking ketone measurements. My basic strategy is that when I feel hungry, I take what seem to me small portions of meat, relative to what I had been eating, and eat lots of fat for satiety. If I start feeling more hunger and fat doesn’t relieve it, I eat a little more meat. What it lacks in definition, it at least makes up for in simplicity.

I started this on Monday, but the next day I was disappointed to discover that I had carelessly broken my Precision Xtra, and so I couldn’t actually measure blood ketones. But I found a link to order a free one. It arrived yesterday, and I am delighted to report that I had a blood ketone measurement of 3.1! That’s significantly higher than any previous measurement, and I retested later with very similar results, so I don’t think it was an error.

Lifting

The other tack I’m taking is to start lifting weights again. It’s been maybe a year and a half since the last time I was regularly lifting.

Weight lifting is probably like aerobic exercise, in that by itself it doesn’t lead to fat loss. For example, take a look at this typical, recent study. Its abstract points out that the participants who did a combination of aerobic exercise and weight training for 30 minutes, 5 days a week, lost “significantly more” fat than those who did only one of those. The way the study is written, and the data reported, distract from the fact that these people lost only about 3.3 pounds over 3 months of this intervention. This is in people who need to lose some 60 pounds of fat to be healthy. Just imagine yourself 60 pounds fatter than you want to be, committing to 5 days a week of probably commuting to a gym and working out week after week, and coming back 3 months later to find that you have lost 3.3 pounds. It’s not something I would tout as particularly effective. Assuming it kept going at that rate (which is unlikely), it would take four and a half years to get to a healthy weight. Certainly, four and a half years down the road, it would be better to have lost fat at that rate than not to have, but again, the long-term effects are unlikely to be linear.

The reason for this is that weight composition is a function of your hormonal state, and the effect of the food you eat is by far the dominating factor.

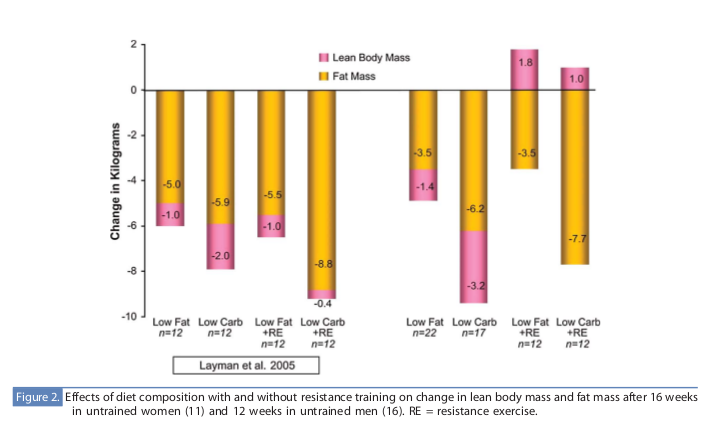

If you combine resistance training with a fat loss diet, though, the effect is to at least preserve lean body mass, and possibly also increase fat loss. This is true even of non-ketogenic diets. Unfortunately, there are very few studies that compare ketogenic diets with and without resistance training. This review reports on two relevant studies. The first compares what it calls low-fat and low-carb diets with or without resistance training. Even though the “low-carb” diet was nowhere near ketogenically low (38:30:32 percent of carbohydrate to protein to fat as opposed to 61:18:26 in the low fat group), the results are striking:

In men the difference between either diet alone and that diet + resistance training meant at least as much fat loss but also a gain in lean mass instead of a loss. Women lost lean mass either way, but lost very little in the lower carb + resistance training situation.

In the same paper, Volek reports the results of a similar study he performed in men only. This time the low carb condition was actually low carb. (They say < 15%, which sounds a bit high, but they also say it was ketogenic, which is what we were really interested in anyway.) Low fat was < 25% fat. Only the difference in percent body fat was reported:

| Low fat | Low fat + RT | Low carb | Low carb + RT |

|---|---|---|---|

| -2.0% | -3.5% | -3.4% | -5.3% |

My lifestyle is not very conducive to scheduling long outings to child-unfriendly environments. This time I’ve decided to do short routines at home using body weight and some free weights. I’m rotating parts so I can do it every day, which is easier on my habit-forming abilities.

I’ll check back in next month, and let you know what happened.